1.1 The Story of Creative Commons

To understand how a set of copyright licenses could inspire a global movement, you need to know a bit about the origin of Creative Commons.

Learning Outcomes

- Retell the story of why Creative Commons was founded

- Identify the role of copyright law in the creation of Creative Commons

Big Question / Why It Matters

What were the legal and cultural reasons for the founding of Creative Commons? Why has CC grown into a global movement?

CC’s founders recognized the mismatch between what technology enables and what copyright restricts, and they provided an alternative approach for creators who want to share their work. Today that approach is used by millions of creators around the globe.

Personal Reflection / Why It Matters to You

When did you first learn about Creative Commons? Think about how you would articulate what CC is to someone who has never heard of it. To fully understand the organization, it helps to start with a bit of history.

Acquiring Essential Knowledge

The story of Creative Commons begins with copyright. You’ll learn a lot more about copyright later in the course, but for now it’s enough to know that copyright is an area of law that regulates the way some products of human creativity — such as books, academic research articles, music, and art — are used. Copyright grants a set of exclusive rights to a creator, so that the creator has the ability to prevent others from copying and adapting her work for a limited time. In other words, copyright law strictly regulates who is allowed to copy and share with whom.

The internet has given us the opportunity to access, share, and collaborate on human creations (all governed by copyright) at an unprecedented scale. The sharing capabilities made possible by digital technology are in tension with the sharing restrictions embedded within copyright laws around the world.

Creative Commons was created to help address the tension between a creator’s ability to share digital works globally and copyright regulation. The story begins with a particular piece of copyright legislation in the United States. It was called the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA), and it was enacted in 1998. It extended the term of copyright for every work in the United States—even those already copyrighted—for an additional 20 years, so the copyright term for individuals equaled the life of the creator plus 70 years.[1] (This move put the U.S. copyright term in line with some other countries, though many countries remain at 50 years after the creator’s death to this day.)

Fun fact: the CTEA was commonly referred to as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act because the extension came just before the original Mickey Mouse cartoon, Steamboat Willie, would have first fallen into the public domain.

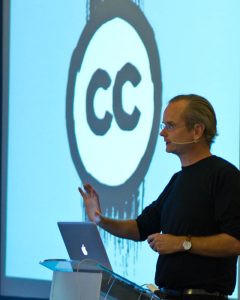

Larry Lessig giving #ccsummit2011 keynote”. DTKindler Photo. CC BY 2.0 Unported

Stanford Law Professor Lawrence Lessig believed this new law was unconstitutional. The term of copyright had been continually extended over the years. The end of a copyright term is important—it marks the moment the work moves into the public domain for everyone to use for any purpose without permission. This is a critical part of the equation in the copyright system: limited copyright terms ensure that copyrighted works eventually move into the public domain and thus join the pool of knowledge and creativity from which we can all freely draw to create new works.

The part of the new law extending copyright protection on existing works was also hard to align with the historical purpose of copyright, particularly as it is written into the U.S. Constitution—to create an incentive for authors to share their works by granting them a limited monopoly over them. How could the law possibly further incentivize the creation of works that already existed?

Lessig represented a web publisher, Eric Eldred, who had made a career of making works available as they passed into the public domain. Together, they challenged the constitutionality of the Act. The case, known as Eldred v. Ashcroft, went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Eldred lost.

Enter: Creative Commons!

Inspired by the value of Eldred’s goal to make more creative works freely available on the internet, and responding to a growing community of bloggers who were creating, remixing, and sharing content, Lessig and others came up with an idea. They created a nonprofit organization called Creative Commons and, in 2002, published the Creative Commons licenses—a set of free, public licenses that would allow creators to keep their copyrights while sharing their works on more flexible terms than the default “all rights reserved.” Copyright is automatic, whether you want it or not. While some people want to reserve all of their rights, many want to share their work with the public more freely. The idea behind CC’s open licensing was to create an easy way for creators who wanted to share their works in ways that were consistent with copyright law.

From the start, Creative Commons licenses were intended to be used by creators all over the world. The CC founders were initially motivated by a piece of U.S. copyright legislation, but similarly restrictive copyright laws all over the world restricted how our shared culture and collective knowledge could be used, even while digital technologies and the internet have opened new ways for people to participate in culture and knowledge production.

Watch this short video, A Shared Culture, to get a sense for the vision behind Creative Commons.

Since Creative Commons was founded, much has changed in the way people share and how the internet operates. In many places around the world, the restrictions on using creative works have evolved and increased. Yet sharing and remixing are the norm online. Think about your favorite video mashup or even the photos your friend posted on social media last week. Sometimes this type of sharing and remixing happen in violation of copyright law, and sometimes they happen within social media networks that do not allow those works to be shared on other parts of the web.

In domains like textbook publishing, academic research, documentary film, and many more, restrictive copyright rules continue to inhibit creation, access, and remix. CC tools help to solve this problem. Today Creative Commons licenses are used on over 2.5 billion works online across 9 million websites. The grand experiment that started over 20 years ago has been a success, including in ways unimagined by CC’s founders. You can further explore key events from CC’s dynamic history on our interactive timeline.

While other custom open copyright licenses have been developed in the past, we recommend using Creative Commons licenses because they are up to date, free to use, and have been broadly adopted by governments, institutions, and individuals as the global standard for open copyright licenses.[2]

In the next section, you’ll learn more about what Creative Commons looks like today—the licenses, the organization, and the movement.

Final remarks

It is in the nature of modern digital technologies, particularly networked ones, to copy and distribute widely creative works. But copyright laws have not fully adapted to this new reality in which we live and share content. Creative Commons was founded to help us realize the full potential of the internet by giving creators more control over how they legally share and use creative works.

- Note: works of corporate authorship are given different terms of copyright protection: in the US, this is typically 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever ends first. ↵

- There are many other open licenses not written by CC that are appropriate for open publishing, but some licenses contain burdensome restrictions on reuse that impose unsuitable requirements or risks. It is always advised to be familiar with the text of a license, particularly the restrictions and requirements for reuse, before making use of licensed material. ↵