2.2 Global Aspects of Copyright

Copyright laws vary from country to country, yet international agreements on copyright set minimum standards for copyright around the world, in effort to standardize copyright laws.

Learning Outcomes

- Learn how the copyright laws of your country may differ from those of other countries

- Identify major international treaties and efforts to harmonize laws around the world

Big Question / Why It Matters

Although copyright laws differ country to country, the internet has made global distribution and sharing of copyrightable works possible with the click of a button. What does that mean for you, when you share your works on the internet and use works published by others outside your country? What law applies to a video taken by someone from India during their travels to Kenya and then posted to YouTube? What about when that video is watched or downloaded by someone in Canada?

Copyright law is locally implemented by every country around the world. In an effort to minimize complexity, governments have signed international agreements to harmonize some of the basic elements of how copyright works across the globe. This means there are fundamental international principles local copyright laws need to follow.

Personal Reflection / Why it Matters To You

When you publish or reuse something online, have you ever thought about what law applies to you? Does it make sense to you that different people should have different limits to what they can do with your work based on their geographic location? Why or why not?

Acquiring Essential / Knowledge Introduction to the Global Copyright System

International laws

Every country has its own copyright laws, but over the years there has been extensive global harmonization of copyright laws through treaties and multilateral and bilateral trade agreements. These treaties and agreements establish minimum standards for all participating countries. This system leaves room for local variation, as many countries enact laws that grant protections above what is required.

These treaties and agreements are negotiated in various fora such as the World Intellectual Property Organization (known as “WIPO”), the World Trade Organization (known as the WTO), and in private negotiations between select countries on free trade agreements.

Two bedrock principles underlie the international patchwork of laws and agreements.

- Territoriality is the notion that a government has no power to govern activities that fall outside of its borders. Copyright is territorial in nature, which means copyright law is enacted and enforced through national laws. Those laws are supported by national copyright offices, which in turn support copyright holders, allow for registration, and provide interpretative guidance.

- National treatment is a rule of non-discrimination. Under this rule, a country must grant foreign authors no less favorable treatment than it grants its own nationals.

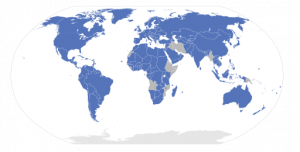

The signatories of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, as of March 2024. Map by Di (they-them) on Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0

One of the most significant international agreements is the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, concluded in 1886. The Berne Convention has since been revised and amended on several occasions. WIPO serves as administrator of the treaty and its revisions and amendments, and is the depository for official instruments of accession and ratification. Today, more than 181 countries (as of August 1, 2024) have signed the Berne Convention. This treaty (as amended and revised) lays out several fundamental principles upon which all participating countries have agreed. One of those principles is national treatment, as described above. That is, all countries must give foreign works the same protection they give works created within their borders, assuming the other country is a signatory. Below is a map showing (in blue) the signatories to the Berne Convention as of 2024.

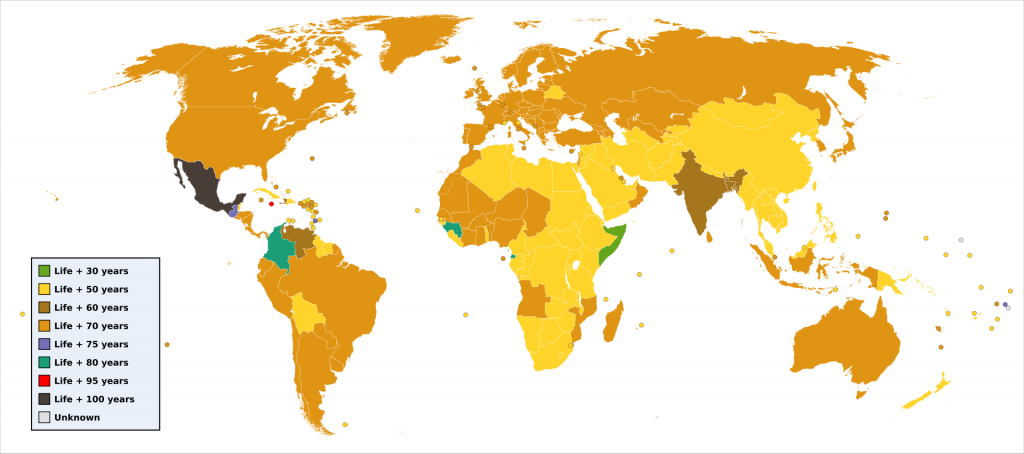

Additionally, the Berne Convention sets minimum standards – default rules – for the duration of copyright protection for creative works, though some exceptions exist depending on the subject matter. The Berne Convention’s standards for copyright protection dictates a minimum term of life of the author plus 50 years. Because the Berne Convention sets minimums only, several countries have established longer terms of copyright for individual creators, such as “life of the author plus 70 years” and “life of the author plus 100 years.” Review the Wikipedia article on copyright term, and view the page that lists the duration of copyright based on country. The map below shows the status of copyright duration around the world as of 2022.

The Berne Convention also prohibits the use of legal formalities as a condition to copyright protection for foreign works. For example, a country cannot require you to pay for a registration in order to obtain copyright there. While most countries have eliminated the use of such formalities as a condition to copyright protection, it should be noted that the Berne Convention does not prohibit a work’s country of origin from doing so.

Worldwide map of copyright term length, as of December 2022. Map by Yodin on Wikimedia Commons, based on an original image by Balfour Smith at Duke University. CC BY 3.0

In addition to the Berne Convention, several other international agreements have further harmonized copyright rules around the world. [1] Thanks to these harmonization efforts, the general operation of copyright laws is the same around the world; however, it’s worth noting that there are differences in the way copyright law is enacted and enforced due to national laws.

What law applies to my use of a copyrighted work?

Generally, the rule of territoriality applies: national laws are limited in their reach to activities taking place within the country. This also means that, generally speaking, the law of the country where a work is used applies to that particular use. If you are distributing a book in a particular country, then the law of the country where you are distributing the book generally applies.

By example: if you are a Sri Lankan citizen traveling to Germany and using a copyrighted work in your PowerPoint presentation, then German copyright law normally applies to your use. With webinars hosting speakers from multiple countries, or PowerPoints presented in multiple countries, it can become complex to determine applicable copyright laws. To avoid confusion, we recommend using resources that are CC licensed, or creating one’s own (diagrams, images or other creative content) rather than copying other resources.

The rule of territoriality also applies for public domain rules. A work might be in the public domain in one country, but not in another one. For example, all the works published between 1925 through 1977 in the US without a copyright notice are in the public domain in the US, meaning that anywhere else in the world they are likely in copyright, depending on when the author died.

As it is shown in the map above, different countries apply different terms of protection. To know which term you should apply for the use of a foreign work in your country, the easiest way is to check whether the country where you want to use the work applies the “rule of the shorter term”. This rule is an exception to national treatment. Under the rule, the term that applies to a given work should not exceed the term it receives in its country of origin, even if the country where protection is claimed allows for a longer duration of copyright.[2]

What law applies when sharing works on the internet?

So what happens when the work is being shared on the internet? How does “territoriality” apply? Can I safely share a work that is in the public domain in my country but might not be in the public domain elsewhere?

Copyright and public domain determinations are dependent on jurisdiction. When you are working in only one jurisdiction, this is relatively easy. Generally speaking, users of copyrighted or public domain works should follow the law of the country in which they are making the copyright determination. So, if you are part of an institution working in Mexico, then you should follow the law of Mexico to make your copyright determinations. But what happens when you are working on an international, collaborative project?

It can be complicated to determine which law applies in international collaborations. One of the benefits of Creative Commons licenses is that they provide simple instructions on how works can be used everywhere. And since the CC licenses and tools are translated in many languages, it means that the user of the work can easily understand those conditions in their own language. The conditions of the CC licenses are also enforceable everywhere.

Final remarks

Even though global copyright treaties and agreements exist, there is no one “international copyright law.” Different countries have different standards for what is protected by copyright, how long copyright lasts and what it restricts, and what penalties apply when it is infringed.

- International agreements include the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)—negotiated by members of the World Trade Organization in 1994, and the WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT)—negotiated by members of the World Intellectual Property Organization in 1996. These agreements address similar issues and also new IP-related issues not covered by the Berne Convention. ↵

- However, the rule of the shorter term for works that are in the public domain in the US due to failure of registration may not apply in other countries. The works tend to be considered under copyright in other jurisdictions different from the US. ↵