5.3 Preparing the Collections

Among GLAMs’ competing priorities, copyright may not be at the top. But copyright is a fundamental part of everyday activities at these institutions, particularly when it comes to digitization and open access projects. Here is a basic overview of some of the important considerations about copyright and digital collections.

Big Question / Why It Matters

Why is copyright so important when discussing open access to cultural heritage? Cultural heritage institutions are commissioned with the task to preserve, disseminate and educate about objects, items, and collections in which they, for the most part, do not own the copyright. Copyright law makes some of these tasks very challenging, particularly in countries where exceptions and limitations do not cover basic activities, such as reproduction for the purpose of preservation. Copyright must be addressed at every institutional level — whether in everyday activities, at the beginning of a digitization project, or during the design of an open access policy. Informing users about how they might be able to reuse the digitized copies of the works available is crucial for any open access policy.

Learning Outcomes

- Describe how the basics of copyright apply to your collection and non collection materials

- Explore tools and techniques that will help you conduct your own copyright research

Personal Reflection / Why it Matters To You

Have you ever searched online for a specific image or other type of work and found a digital reproduction whose terms and conditions did not allow you to use it? Have you chosen to use an alternative image, because the terms and conditions for using that other image were clearer?

Acquiring Essential Knowledge

When we explored the benefits and challenges of open access, we briefly talked about the reasonable fears that some institutions face around liability. Some institutions adopt a more conservative approach to copyright as a result.

This happens because GLAMs steward works in which they often do not own copyright. In addition, copyright is automatic and lasts a very long time. Even when limitations and exceptions can help institutions achieve their mission of providing access, it can still be quite challenging to identify who owns copyright over a work, and how long the work will be protected before it falls into the public domain, at which point an institution can freely make a copy or share it online.

Here are some reminders:

- Owning a physical copy of the work does not give you copyright over the work. The fact that an institution has a certain control of the physical object does not give the institution any copyright in the work.

- A work receives copyright regardless of aesthetic merit. Copyright law is guided by the principle of “esthetic neutrality.” This means that the only factor for granting copyright protection is whether the work is an original expression made by an author.[1] This is particularly relevant for archives, who might think that some of the works that they steward are not protected because they are not “artistic.” For the purposes of copyright law, however, this is not relevant. This means that it is likely that vast amounts of documents held in archives will be indeed protected as copyright works regardless of their artistic or esthetic merit, provided they are considered original.

- Digitization should not create new rights over the work. Faithful digital reproductions do not create anything original. On the contrary, digitization of works is usually a very highly standardized technical process that tries to capture the original work with as much fidelity as possible.

- There are barely any creative choices made by the person creating digital reproductions (if there is a person involved at all). This is still a contested issue in the cultural heritage sector, as we will explore further on this section when we talk about the layers of digital works.

- Standardization and legal interoperability are crucial for discoverability. Using standardized tools such as CC0, the Public Domain Mark and Rights Statements bring much more value than simply making a statement that says “This work is in the public domain”. As you might remember from Unit 3, CC licenses and tools were designed to be machine readable. This is one of the most compelling reasons to use CC tools and licenses (and Rights Statements): because they are designed to “speak” a language that machines can understand, and therefore allow for better search functionality. Furthermore, these are tools that users can understand easily, unlike having to read through complicated terms and conditions. Lastly, CC licenses and tools are multilingual — they are available in dozens of languages. This makes it easier for international reuse!

General rights workflow for digitization projects

There are several tools that can help you create your own workflow for integrating copyright considerations into your digitization projects. Here are some important considerations:

-

- Determining the copyright status of objects should be considered at the beginning of any digitization project, at the planning stage. Many projects leave copyright decisions to the end, just to find out that some of the items that have been digitized cannot be made available due to copyright restrictions. This might be particularly problematic if making works openly available is a funding requirement, as many funders currently require.

- Document and record any decision you make related to the copyright status of items in your collection. This is good practice for several reasons. It helps inform future decisions regarding a collection inside your own institution, and makes your decision transparent to others. It can help you potentially avoid duplication of work. Having a tool like a DAMS (Digital Asset Management System) is helpful to record these decisions, but even a spreadsheet can also serve as the place where you register them.[2]

- Everyone working with collections should have at least basic knowledge of what copyright is and how it works or be able to reach out to someone who does. Ideally, every level of the staff involved with digitizing and sharing materials online should understand what copyright is and how it functions — not every aspect of copyright law, but basic concepts and practical implications.

- All your copyright decisions are territorial. This means that even when you are making decisions to make the works available online (and therefore to be displayed globally), you should follow your understanding of applicable law (typically the law of the jurisdiction where the works are being digitized and uploaded). It is up to users of other countries to determine whether and how they can make use of those works based on the law that applies to their reuse.

Clarify copyright at the time of acquisition

This point is relevant to any project, not only digitization ones. It is always better to clarify copyright at the time of acquisition; that is, whenever you commission or receive a work or a collection. Ideally, you should make a clear determination of all rights and their respective holders for every work or collection entering your institution. Rights transfers, such as grants and licenses, as well as reuse permissions, can be negotiated upon acquisition. For example, the Highsmith Archive at the U.S. Library of Congress is based on a set of photographs donated by photographer Carol Highsmith, who allowed for anyone to have access to the photos and make copies and duplicates as long as she is credited as the author, similar in its terms to a CC BY license.[3]

An institution can also make sure to negotiate the copyright terms under which both the institution and the public can use the collection before accepting donations or otherwise acquiring works. If there is no room for negotiation, at least the copyright conditions should be made clear. The Highsmith Archive example above represents an ideal situation, where the author clarifies rights and permissions from the beginning, and even more so, allows for unrestricted access. But intermediate steps, where the institution is allowed to make copies for preservation purposes and to display high-resolution copies of the work online, are examples of what could be clarified right from the beginning — such activities are sometimes allowed under an exception in certain jurisdictions and therefore permission from the author is not required. Another example of where you might clarify copyright at the point of acquisition is if you are commissioning a work. An agreement should clearly state who will own the rights in the commissioned work.

In certain cases it may be difficult to do such agreements. The situation is particularly dramatic for archives. There are archives that have rescued entire collections from the trash; archives that receive donations composed of multiple materials from very different sources by an heir or relative of the author, etc. In those cases, the best option may be to conduct a rights clearance process or follow the steps established in the risk management assessment tool (see the subsection below, “Managing risk”).

Managing risk

In general, every GLAM needs to assess its level of comfort with risks associated with copying works and making them available. Risk assessment is particular to each institution, and in some cases it might be particular even to specific projects. It is important that a risk assessment policy is written down and that you follow it.

Dalhousie University currently offers their “University Libraries’ Copyright Assessment Tool” under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. In this tool, risk is categorized as high or low. Other institutions take a more granular approach, identifying high, medium, and low. Again, the decision to take this approach will depend on your institution.

Generally speaking, another important question that you need to answer is what is the intended use for the work. A very interesting resource to check is the Code of Best Practices for Fair Use in the Visual Arts, the result of a collaboration between the College Art Association of America and the Center for Media and Social Impact at American University. Even when this Code talks about fair use and particularly in the visual arts, some of the questions and principles raised can be helpful to design your own risk assessment.

If you are interested in seeing how other institutions approach risk, check the research carried out by Victoria Stobo, Kerry Patterson and Ronan Deazley on “Digitisation and Risk” for their project on Digitising the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks.

Important questions that you need to ask with respect to your own risk assessment are related to the nature and character of the works, the purpose for which they were created, visibility and relevance of the author or rightsholder, among others. And importantly, you need to make sure to have a procedure to fix any mistake that you inadvertently might have made in the copyright research and clearance process. This shows good faith towards both the rightsholders and the general public.

Managing risk in third-party platforms

If you are using a third-party platform, you need to read through the platform’s terms and conditions to decide whether the platform is appropriate for what you intend to do with the digital objects and if it abides by your own legal terms.

For example, Wikimedia Commons only accepts content that is in the public domain or available under particular open licenses. If an administrator of Wikimedia Commons (normally, a community appointed person) finds that there is a violation of the copyright policy, they will remove the content. To prevent this, explore their FAQ to understand whether you can upload works to Wikimedia Commons.

Understanding the layers of digital reproductions

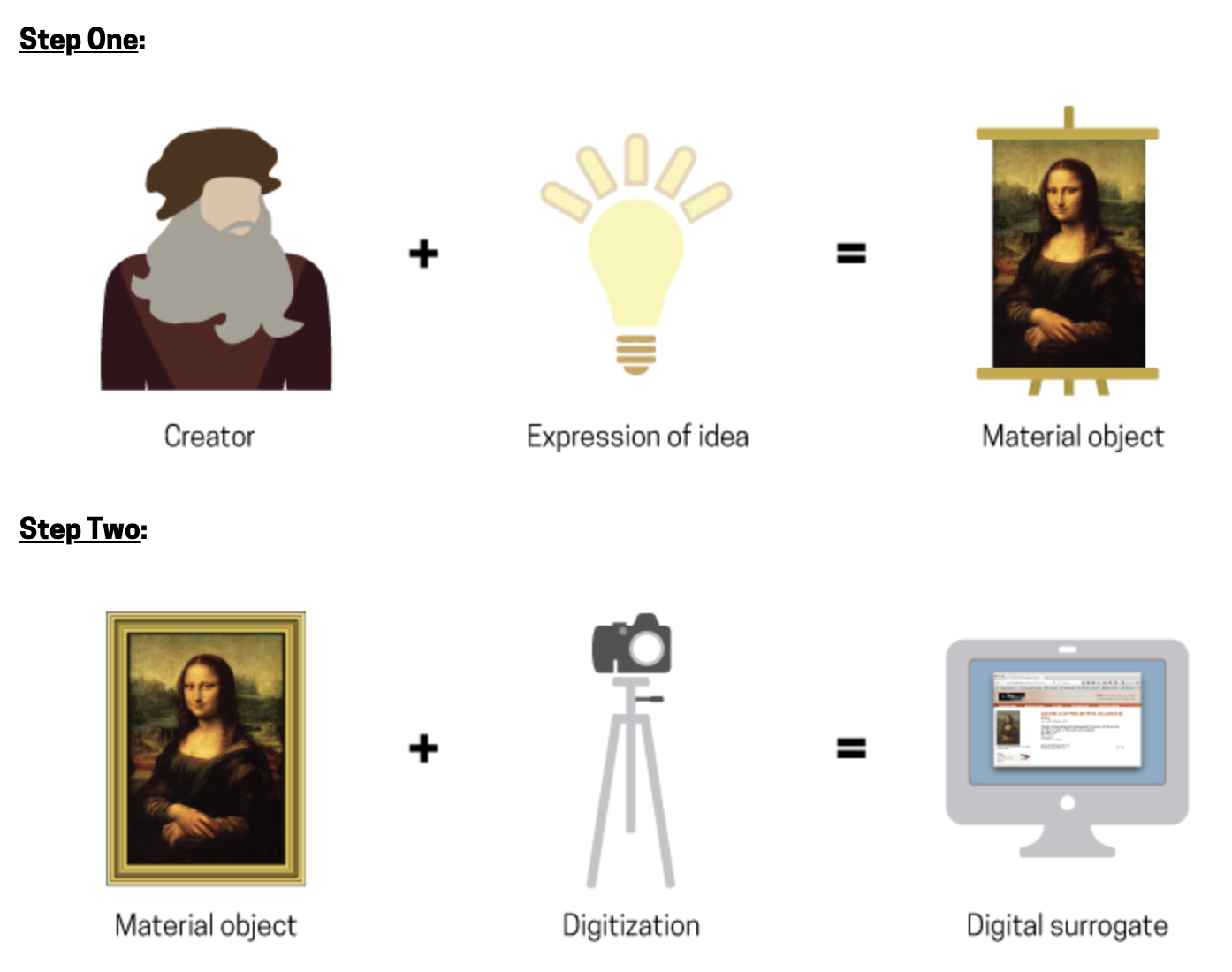

Infographics on material objects and digital surrogates by Andrea Wallace and Ronan Deazley, CC BY, Display At Your Own Risk, 2016.

In the open culture context, it can be hard to understand the relationship between a physical work and the digital reproduction (or “digital surrogate” or digital “twin”) of that same physical work. This relates to the definition of open access for digital reproductions, which varies greatly between institutions and even within countries. The infographic above made by Andrea Wallace & Ronan Deazley tries to bring some clarity on the difference between creating a work that will be the subject matter of copyright protection and creating a digital reproduction of that work.

Some countries recognize rights over the digital reproductions of works (whether or not the underlying physical work is protected or in the public domain). These rights can be similar to copyright (i.e., related rights or sui generis rights), and do not affect the public domain status of the underlying work; in such cases the underlying work remains in the public domain while a thin layer of protection is granted over the digital reproduction of that work.

This is where the “originality” requirements might come into play. Mechanical reproductions (the “digitization” part of the infographic), including digital reproductions of artworks, often do not meet the originality requirement to be granted copyright in countries where originality or “modicum of creativity” requirements exist, since they are technical, faithful reproductions . In some cases, they might not involve a person at all and copyright does not arise absent a human “author.”

If your institution is working in a jurisdiction that recognizes such a right, having an open access policy enables you to forgo the rights that you might have over digital reproductions. Preferably, you would do this by releasing the digital reproduction under CC0. This does not affect the copyright status of the underlying work.

It is important to note that this additional layer of rights creates several challenges for reusers and for future copyright clearance professionals. It also leads to inaccurate and invalid rights claims, such as in cases where digital images of public domain works by French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) have been released under a “CC BY-SA” license, implying that there are rights to be licensed out.

For more about the intricacies of copyright, cultural heritage and reproductions in three dimensions (3D scans), watch this 2023 CC webinar.

Collectively, the GLAM community should aim toward more standardization of how they are applying CC licenses and tools as well as Rights Statements to digital reproductions. There are still many institutions that have applied CC licenses to the digital reproductions of works (therefore claiming a copyright over the digital image). Good faith users tend to respect these statements, but using CC licenses for digital reproductions is incorrect and against the spirit of open culture.

Additionally, recent developments in Europe with the implementation of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market, clarify that public domain works must remain in the public domain, and that their digital reproductions cannot be protected by copyright. Article 14 of the DSM reads:

“Works of visual art in the public domain. Member States shall provide that, when the term of protection of a work of visual art has expired, any material resulting from an act of reproduction of that work is not subject to copyright or related rights, unless the material resulting from that act of reproduction is original in the sense that it is the author’s own intellectual creation.”

Still, many institutions erroneously share digital reproductions of public domain materials under CC BY, a problem explored by the OC platform working group on Public domain collections referenced by CC BY to designate collections holders in 2022.

Establishing the copyright status of works

There are two copyright statuses: a work is either in the public domain or it is protected by copyright. Sometimes that is impossible to determine and the work’s copyright status is unknown.

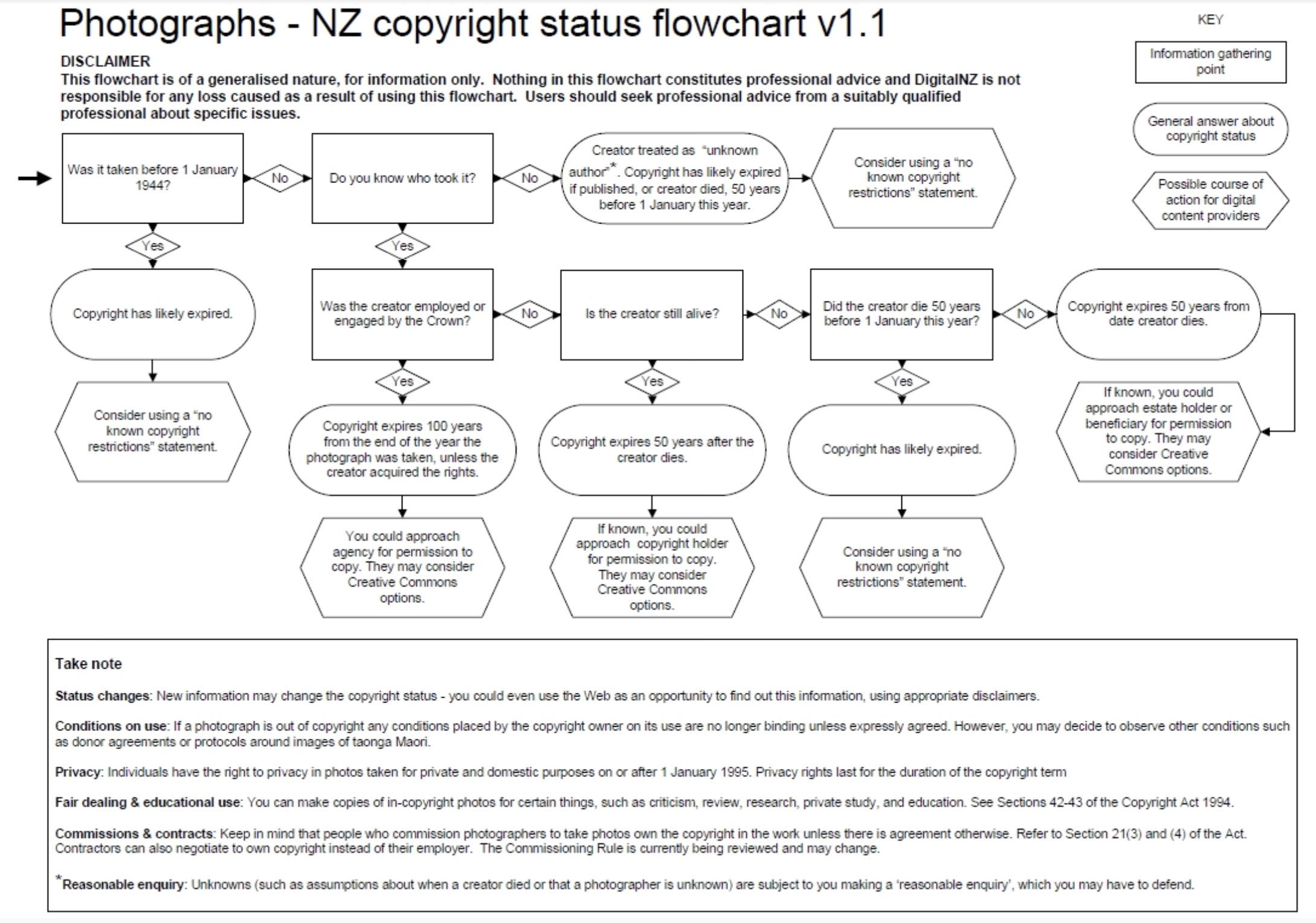

The best way to ensure that your decisions are consistent is to use a copyright chart, a copyright decision tree, or some type of framework for making copyright assessments. One helpful tool that you can use and adapt to your needs is the Copyright Assessment tool developed by Fred Saunderson at the National Library of Scotland. This framework is specifically designed for the Library’s own legal environment, but if you know your local legislation, you can adapt this framework.

Example of a copyright status flowchart. This flowchart was made by Make It Digital New Zealand and therefore applies New Zealand copyright law.

There are many, many other options available on the Internet for different countries, but of course you can decide to create your own. Some examples include:

- Rights Review: An approach to applying Rights Statements from RightsStatements.org

- Connecticut Digital Archive Copyright Guide

- Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States

- A permissions decision tree made by the Smithsonian

- Canadian Copyright Term and Public Domain (PD) Flowchart made by the Copyright Office at the University of Alberta (Canada)

- Out of Copyright (EU)

- Copyright Status Flowcharts | Enabling Use & reuse | Make it Digital New Zealand

What are the differences among all of them? Primarily, their level of detail or complexity. Ultimately, you will want to find or adapt an assessment to meet your practical needs.

Public domain

As a reminder, we have discussed the public domain in Unit 2. To determine whether a work is in the public domain, you will need to take a look at your local law in order to establish both the terms of protection (how long copyright lasts) and the conditions of protection that might affect your materials (for example, some countries make distinctions between unpublished and published works or fixed and unfixed works). A very general overview can be found in “Copyright Rules by Territory,” maintained by the Wikimedia Commons community.

In Unit 2 we also mentioned the principle of national treatment, meaning that countries grant the same protection to foreign authors to those that they grant to their national authors. The “rule of the shorter term” is an exception to national treatment. Under the rule, the term that applies to a given work should not exceed the term it receives in its country of origin, even if the country where protection is claimed allows for a longer duration of copyright.[4]

Public Domain Mark

Public Domain Mark

Whenever a work is in the public domain, you should make sure that it is clear for reusers that this is the copyright status of the work. Mark the digital reproductions of those works with the CC tools: the Public Domain Mark or CC0. It is important that you add machine-readable statements to the digital objects rather than simply stating “the work is in the public domain” so software platforms and search engines can easily identify and retrieve these works.

The difference between the two public domain tools (CC0 and PDM) comes down to whether or not the person or institution applying the tool has any rights in the work and/or its digital reproduction. The Public Domain Mark is a label only and does not have legal effect. As such, it should be used to indicate the lack of any known copyright in the work. CC0, on the other hand, is used to dedicate rights to the public domain and should be used when the person or institution has rights over the work that they want to forgo. In the open culture context, this arises most often with respect to the digital reproduction of public domain works, which can sometimes give rise to copyright protection.[5]

There are tools that allow for searching for authors and works in the public domain. Aside from national and specific databases that might help in that search, you can navigate through Wikidata. If you are familiar with the Wikidata SPARQL Query Service, you can try browsing through the properties “copyright status” and “public domain date.” Curious to know how this works? You can also check the Wikidata pages Help:Copyrights.

The Copyright Offices in some countries have attempted to digitize their registers, allowing one to search through catalogs for a works registration or public domain status. In the US, you can also search through Stanford’s database of Copyright Renewals.

Lastly, it is important to note that national laws will differ about whether moral rights (the rights of attribution and integrity) expire at the same time as the economic rights or whether they are perpetual. Make sure to check your national law to understand how you should treat moral rights.

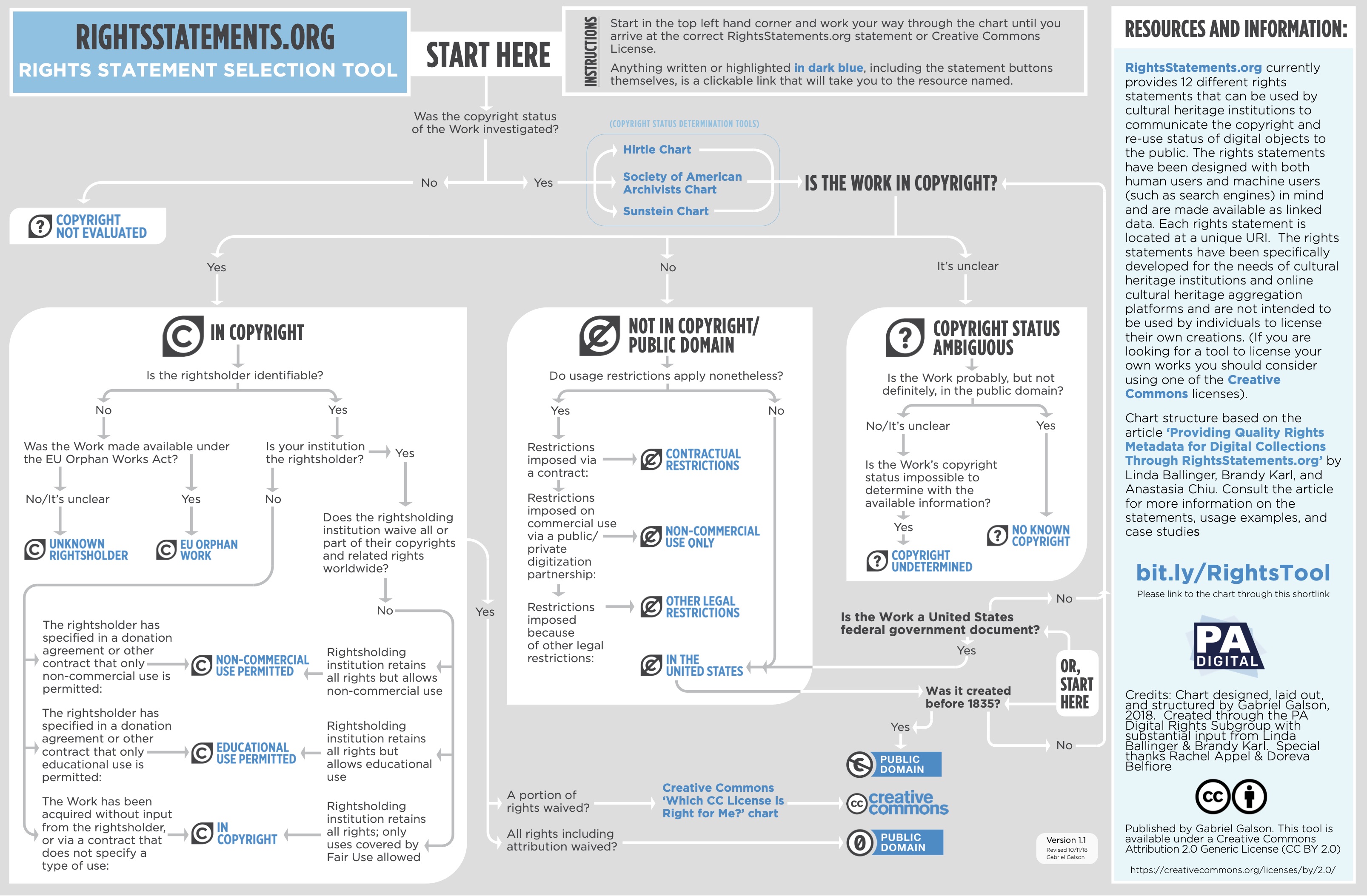

In copyright – Locatable rightsholders

Chart designed, laid out, and structured by Gabriel Galson, 2018. Created through the PA Digital Rights Subgroup with substantial input from Linda Ballinger & Brandy Karl. The chart is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

If a work is in copyright, it does not mean that you cannot display it online. You might not be able to make them openly available, but you can still display it by:

- relying on a limitation and exception under your national law, if and where applicable;

- obtaining permission from the rightsholder;

- entering into a licensing agreement with the rightsholder and/or the collecting society that represents the rightsholder.

Some members of the public tend to think that “online” equals “free for use.” To avoid this, you need to convey the proper copyright status of the digital objects and any permitted uses. For works in copyright that you make available online, there are different ways in which you can mark their copyright status. Important takeaways are:

- CC licenses can only be applied by the copyright holder or with the permission of the copyright holder to works that are in copyright.

- CC licenses are not applicable absent an agreement between the rightsholder and the institution. This means that the rightsholder has to agree to make her work available under a CC license. You cannot use a CC license to convey the copyright status of a work to which you do not hold the rights.

- If you have an agreement with the author that allows members of the public to use the work for non-commercial uses or for educational purposes, you should use the proper Rights Statements for in copyright objects:

- If you display the work by relying on a limitation or exception, follow legal requirements and sector best practices, such as including all the proper credit information, even when posting it on social media or displaying only a low-resolution photo of the work. Include the proper Rights Statements, “In copyright,” to signal that you are making the work available under a limitation or exception.

There are several tools that you can use to know who the rightsholder of a work might be. If you are based in the US, you can use the WATCH database. If you are in Europe, you can use the databases being provided by EUIPO.

The level of digitization of copyright records varies greatly across countries, in part because these are resource-intensive processes. However, an important detail to take into account is that generally speaking Copyright Offices normally have some information about contracts signed by authors and rightsholders, depending on the functions of the Copyright Office according to national law. Whenever in doubt, a good practice is to try to contact your local Copyright Office so they can provide you assistance with understanding how national copyright law works and how to use their contract records.

In copyright – Orphan works

As we saw in Unit 2, copyright protection is automatic, meaning that a work is protected right at the moment at which it is “created”[6] in most countries. Long terms of protection and automatic copyright protection create the ongoing problem of “orphan works,” works that are likely still protected by copyright but whose authors or rightsholders are unknown or impossible to locate.

An example of such a work would be an original photo of a popular alley taken in Germany in the 1960s but with no additional information about who the photographer might be. For archives, orphan works are a particularly acute problem, since for some of them the vast majority of the works they hold are indeed orphan works.

Like other copyright works, in certain parts of the world orphan works can often be used and displayed under limitations and exceptions, and some countries may even have specific exceptions that allow for further uses of orphan works.

Additionally, if you want to display orphan works, you can also implement mechanisms that make it easy for a potential rightsholder to contact your institution in order to take it down if they oppose displaying it.

For orphan works, there are two available Rights Statements:

- For orphan works outside of Europe: IN COPYRIGHT – RIGHTS-HOLDER(S) UNLOCATABLE OR UNIDENTIFIABLE

- For orphan works in Europe: IN COPYRIGHT – EU ORPHAN WORK

Unclear copyright status / Unknown

The last category is “Unclear copyright status / Unknown copyright status.” This is when it is impossible to determine whether the work is protected or not, and who the rightsholder might be. Although in a way these could be considered “orphan works,” they are distinct in that it may be difficult to even tell if they are in copyright to start with.

Other rights or considerations

Aside from copyright, there are other considerations for making works available online. You should avoid posting works that might be culturally harmful: for example, in certain contexts, the display of human remains.

Privacy considerations are also paramount. Tara Robertson outlined an interesting case study in her talk: “Not All Information Wants to be Free: The Case Study of On Our Backs.” Before making information available online, consider: the context in which the information was created; whether there is sensitive or confidential information shared; the purpose for creating that information; and the potential harm that the digitization and online availability might cause.

See Unit 2, section 2.3 for information about Indigenous cultural heritage and traditional cultural expressions.

Releasing Your Original Content

A key component of a comprehensive open access policy is the release of content and materials that you have created under that policy. For example, original research, educational and training materials can be released under a CC BY or CC BY-SA license, or even dedicated to the public domain under CC0. You can use other licenses too, but these are the ones recommended in order to make usability as easy as possible.

You can also release the accompanying information (called “metadata”) of the works that you hold. There are many benefits to openly sharing materials such as catalogs and metadata. This content is particularly useful to provide context and expand open knowledge in different areas of scholarship.

In some countries, metadata is not protected by copyright at all because it is mainly composed of unprotectable facts and usually lacks originality. However, in other countries it might be protected, and in such cases it is recommended to release it under CC0.

Marking and labelling works

Once you have decided which license or tool you will use, it is good practice to mark the items with the license or tool. That will depend on which type of software platform you use: your own website; a DAMS (Digital Asset Management System); or a third-party platform like Flickr or Wikimedia Commons.

It is important in most cases to mark at the item level because sometimes different works in a collection will have different copyright statuses and permissions, and making a blank statement for all the works being displayed (for example through a Terms & Conditions section in your website) might actually not be accurate or appropriate.

Of course, policies and items are related to each other. For example, if you decide to apply a CC BY license to all the content that you produce to the extent possible, that is a policy, but it will be reflected at the item level — ideally every item will be marked with CC BY, and each item that has a different copyright status will be published with a tool, statement or label indicating that different status.

For example, the website with digital heritage run by the National Library of Chile, Memoria Chilena, releases their research under a CC BY-SA license (as you can find in this example), but they make sure to mark each individual work being used and presented with its corresponding public domain status (for example, in the section “Documents,” if you click on a specific document, you find a different statement that signals that they are in the public domain).

Whenever possible, make sure to mark the copyright status of the work at the item level. This will provide greater certainty to users about whether and how they can use any single item.

Final remarks

Copyright inside an institution can be a very tricky matter, but copyright is the cornerstone of every open access release. Understanding some of the nuances and details of copyright when applied to an institution is very important to make sure that it is incorporated from the very beginning in the design of every project that deals with any type of content.

- For more information, see “Threshold of originality”. ↵

- See the generous examples provided by Annabelle Shaw from the British Film Institute “Examples Rights Research Tracker - British Film Institute” and “Example Rights Information - British Film Institute." ↵

- This highlights the importance of using standardised licenses, since they provide users more clarity about what they are allowed and not allowed to do. ↵

- However, do not try to apply the rule of the shorter term for works that are in the public domain in the US due to failure of registration. Those works tend to be considered under copyright outside the US since registration is not a condition of protection. ↵

- See Wallace, A., Euler, E. Revisiting Access to Cultural Heritage in the Public Domain: EU and International Developments. IIC 51, 823–855 (2020). ↵

- Depending on the definition applicable by national copyright law. ↵