5.4 Opening Up & Sharing Collections and Content

Sharing your collections and content comes at the last step on the road towards open access, but it is the one that will prove the value of the decision of releasing collections and content. Engaging with the public takes time and work, and it is important that users understand how they can engage with collections and content.

Big Question / Why It Matters

Laying the groundwork for implementing your open access policy is time consuming and resource intensive, but once done, you can reap the benefits of open access. Communicating copyright policies is crucial to make sure that the public and reusers can understand what they can do with the openly available content. Clear communications allows for different communities to engage with the content and remix and reuse it in new and innovative ways.

Learning Outcomes

- Analyze how copyright policies can be communicated within institutions

- Explore ways in which you can engage with different communities of re-users

Personal Reflection / Why it Matters To You

Have you ever edited a Wikipedia page? Have you ever used an artwork to design a flyer for an event? How did you find out if you could reuse the content? Have you ever been impressed by the ways in which culture can get creatively re-interpreted?

Acquiring Essential Knowledge

There are many ways in which your institution can measure the impact that an open access policy might have. But without a doubt, an important aspect of measuring that impact will be how the content is being used and shared by members of the public.

Not only is it important to identify stakeholders, communities and end users before an open access release, but incorporating them into the planning process will also help you achieve impact. You can also plan to incorporate different stakeholders and users in later stages, according to the resources that you have available.

It is important to make sure your copyright policy actually makes sense for your audience and public.

Understand your environment

When an institution starts to look at implementing open access, it might start with the ambitious goal of “releasing as much content as possible.” However, it is also important to start small and build upon success with incremental steps. For this, exercising due diligence is key. Exercising due diligence requires considering varying factors that may affect your project, including: the type and complexity of the collection you want to release, the size and resources of your institution, and the stakeholders involved.

Each institution is unique, so there is no “one size fits all” approach. However, there are commonalities across institutions, and these are important elements to consider when designing a plan on how to release collections.

Here are some recommendations to help you understand your environment.

- Assess capacity, logistics, resourcing and sustainability. The exercise of assessing the capacity of your institution should lead to a better understanding of the actual resources that you can count on and being realistic about expectations and potential impacts of your open access program. This does not mean that nothing can be done until you have all the resources and technologies in place, but rather that you should plan according to the resources you have available. Important questions should include: Is there any support for open access at your institution? Which shapes does this support take? What are current projects and activities that could help start a conversation about open? Can you start with something small? Do you have in-house capacity to assess and evaluate copyright issues? Do you need to partner with another institution? Are you able to maintain the open access policy and release accessible in the future?

- Test and build pilot projects.

- Identify stakeholders, communities and end users. If you want to involve communities in your project (whatever those communities are), remember that building those relationships takes time and resources too. Even when there are many benefits from crowdsourcing, people volunteering or collaborating in enhancing your digital collection need to feel a personal connection with the institution. You should be able to answer the question: Why is the institution building this digital collection, and for whom? Having clarity on who your end user is will also help guide the activities and steps that you will take for achieving your goals.

- Look for peers, allies and examples. A good way to build your case for open access is by getting in touch with other people that have gone through a similar situation. They might be able to provide you with smart advice. What would they have changed in their approach? What things helped them on their path to open? What worked, and what did not work for them?

- Make your case. Making your case is all about being prepared with the arguments and the supporting data to present to leadership, authorities and colleagues at the institution. But it is also about being able to seize opportunities that might present themselves. For example, several institutions decide to change their policy around open access when they redesign their website. Identify what might be the window of opportunity in your own institution. Maybe a change in technology; a workflow redesign; a departamental re-arrangement, or some other opportunity that might present itself to spark the conversation.

- Persuade colleagues and leadership. Do you know what the concerns of colleagues and leadership are? Take a moment to listen to the concerns and try to connect how implementing open access might help solve some of them. Focus on what colleagues might care about, and do the research to understand if and how open access might come in handy for solving that problem.

Explain your copyright policy

One of the reasons cultural heritage institutions release works and content is an interest in better serving their users and fulfilling their mission. An important aspect of “serving users” is to make copyright policies clear and easy to read for non-legal experts.

CC licenses and tools as well as other labels such as Rights Statements are not a copyright policy: they are practical, legal tools or labels to practically implement an institution’s copyright policy. Your copyright policy reflects your decisions on copyright issues and governs the use and reuse of content.

CC licenses and tools help because they offer a simple way for users to understand that copyright policy. But it is also good practice to explain your copyright policy on your website, as a way to give users different access points to figure out how they might be able to reuse works and content.

Your copyright policy should also explain how users should credit you as the steward of the collection. Crediting an institution is good practice by users and shows good faith on those institutions that decide to openly share their collection. We recommend including a sample attribution statement that users can simply cut/paste in order to credit you appropriately. For examples, see our 2024 report: Nudging Users to Reference Institutions When Using Public Domain Materials, Creative Commons Guidelines.

For a great example of a clear copyright policy, see the National Library of Scotland page on Copyright. In that page, you can see that the NLS also refers to the content that they currently have hosted in other platforms, such as Flickr.

Build an FAQ

FAQs are valuable instruments to clearly outline your policy and explain additional information about how you are making items on your collection available. The basic information should include a clear indication of what users can do according to the tools and labels you might be using and when they should conduct additional rights research. Another option is to include information about the files you are making available, i.e., format, resolution, size or quality.

There are several good examples to look at. The Nationalmuseum in Sweden has built the information provided to users in their “Rights and Reproductions” section. Take a moment to look at its policy. What do you see?

You will find that in this case the Nationalmuseum decided to include the license deed information directly in the FAQ (remember what we saw in Unit 3 around the three layers of the CC license?). They also included very specific information on how they expect users can attribute them.

Additionally, aggregators can decide to write their own FAQ. See for example the one that Europeana did on Reusability to explain the different categories that you can search for and how a user should interpret the reuse licenses. Other examples include the DigitalNZ that has a section on Copyright, Accessibility and Privacy. These are good examples of how different aggregators might approach copyright questions differently.

The Smithsonian has a long FAQ that also includes relevant information about its open access initiative. Take the time to look at the policy. In this one, we want to highlight one of the questions:[1]

In this way, the Smithsonian also solves a very pressing concern that some cultural heritage institutions have around the accuracy of their metadata.

Consult the Survey of Open GLAM practices and policies. Go to Column M, “Rights policy or terms of use.” Organize the spreadsheet by your country and explore how institutions in your country are building their FAQs.

Make your expectations on re-use clear

Inform your user what your minimum expectations around re-use might be. As we have seen in previous units, you cannot add additional restrictions to public domain works or to works that you decide to release under a CC license. Some of the important points described in the FAQ, “Alterations and additions to the CC license,” will apply:

- you cannot ask for an exact placement of the license;

- you cannot add additional restrictions on the license.

Moreover, the biggest favor you can do for your users is to maintain terms and conditions that are as clear and straightforward as possible.

In several countries, users are not obliged to include attribution for public domain works. You can, however, ask your users to adopt the best practice of properly crediting the institution when reusing the work. You can also provide sample citations or attribution statements indicating how you wish the works to be credited. Check out this example by The Wellcome Collection, a museum and library in the UK.

Take a look again at the Public Domain Guidelines created by Creative Commons. Those Guidelines are licensed under a CC BY SA license, so you can reuse them and adapt them as you see fit to serve your own purpose (and Europeana has translated them into several languages!). Educating your users on how you expect them to abide by good faith will go a long way to help prevent some uses that you might find distasteful.

Maintain consistency across websites and third-party platforms

One of the biggest challenges is to maintain a consistent open access policy across multiple websites and third-party platforms. Such websites could include proprietary or open source digital collection software (e.g. Access to Memory, Collective Access, Islandora, Dspace), which include varying abilities to represent rights metadata. In some cases, institutions might maintain more than one website. For example, a particular research project that digitized a specific collection might need its own stand-alone website. To the extent possible, those websites should try to replicate the same policy as the main website of the institution to avoid confusion.

Institutions that choose to go open access also tend to put their images into multiple platforms. Third-party platforms can be challenging, because some platforms might support CC licenses and tools, while others might not. Social media platforms can also be challenging. If you are interested in seeing how different institutions adopt social media strategies to properly attribute authors and credit institutions, check out this conversation between professionals at Europeana, the Indianapolis Museum of Art and The Getty Museum.

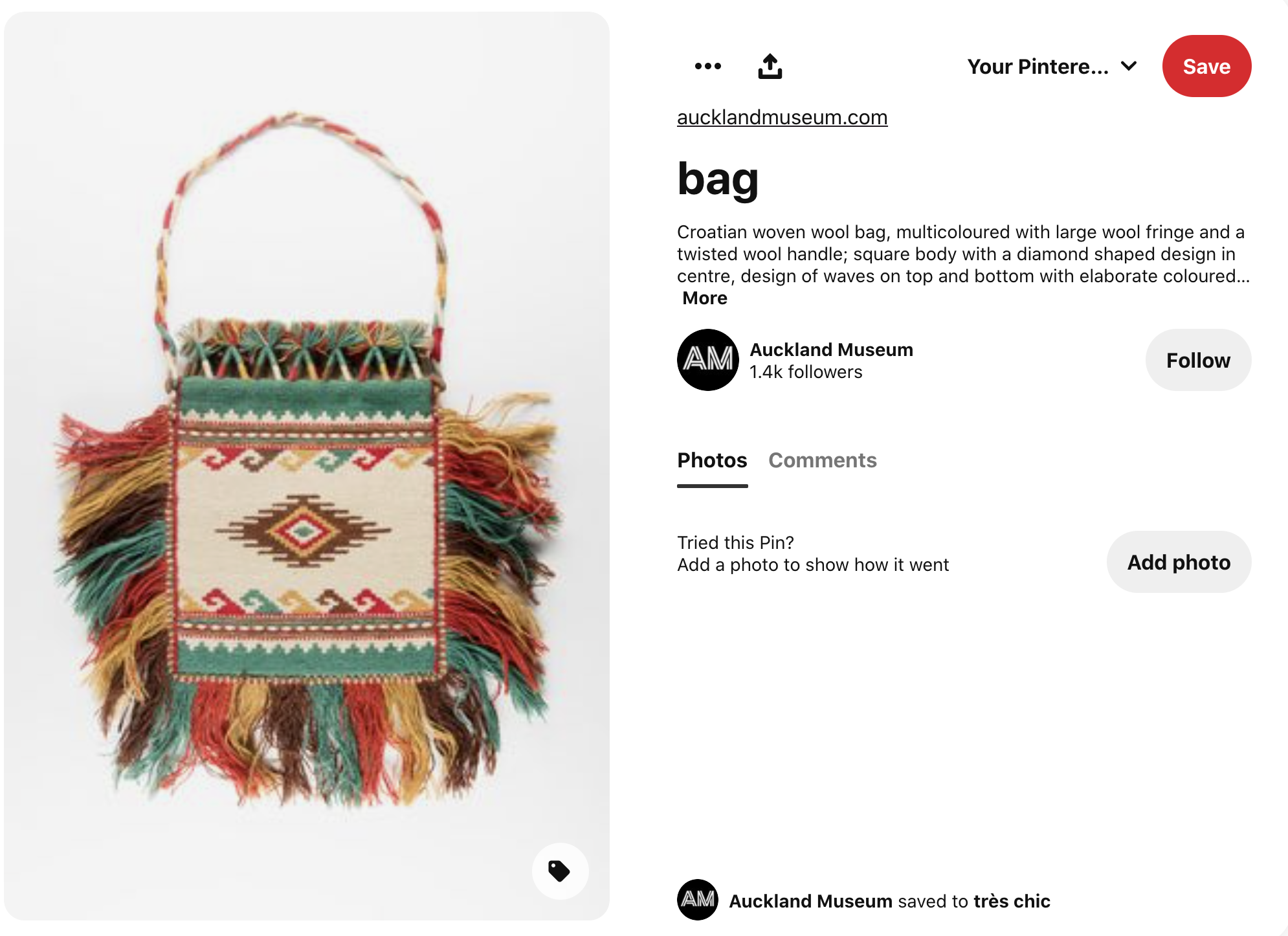

The best way to ensure attribution by reusers is to link back to your institution’s website if the platform does not allow for a proper mechanism to acknowledge you. For example, the Auckland War Memorial Museum has a Pinterest account; take a look at this Croatian woven wool bag.

Croatian Woven Wool Bag, Auckland Museum, CC BY.

In this case, the Auckland War Memorial Museum decided to manually indicate the CC BY rights in the description box next to the photo. They also included a link back to the item on their collection website, which then leads to the user to see the same reference to the CC BY license when browsing through the objects.

In some third-party platforms like Flickr, Sketchfab and Wikimedia Commons, CC licenses and tools are supported (i.e. “built-in” the platform), or they might even have their own statements (called “templates” in Wikimedia Commons). Wikimedia Commons in particular has a high threshold for accepting photos per their copyright rules. They only accept works identified to be in the public domain or voluntarily released under a Wikimedia Commons-compatible CC license by the rightsholder.

However, even when the copyright statement is mandatory and already standardized by a template, there is still some room for variation. See for example how the National Archives of Brazil are releasing their collection on Wikimedia Commons. Most of their items are marked as being in the public domain, with a special note that states, “Please attribute as: Public domain / Arquivo Nacional Collection,” as you can see in this example.

The Cleveland Museum of Art is another example of an organization releasing their collections on Wikimedia Commons. Check out this sculpture, “Winter,” by an unknown artist. In this case, the Cleveland Museum of Art decided to link back to their open access initiative on their own website.

And last but not least, we have Flickr. Flickr has a special section for GLAMs that want to release their collections called Flickr Commons, now managed by the Flickr Foundation. Flickr offers participating institutions to apply a Public Domain Mark as a way to identify works that are in the public domain. As in Wikimedia Commons, institutions can choose to add additional information on each of the images.

| Read this analysis by Douglas McCarthy, “Rights Statements: link rot in Flickr Commons.” In that article, Douglas identified several institutions whose rights policy returned a “404 – Page not found” error message. This is particularly problematic, because reusers need to be able to retrieve the conditions in which they were making use of the work. |

Finally, more and more institutions are choosing to build APIs for uploading and releasing their open access content. If you have the resources to build an API, an important consideration is its accessibility over time. As this article explains, not maintaining these APIs might make information disappear from the internet or make some pieces of software code impossible to use.

Engage with communities

The communities that you engage with are the ones that will prove the impact of the open access policy and they are the ones that will allow you to put in practice some of the benefits explored in this unit. Communities are also the ones that will take your content, put it in different platforms, and enhance your collection by finding new, different, and innovative ways to use it and reuse it.

Integration into external interfaces

An important part of making your content and collection available is being able to put your work out there in other channels, such as Wikimedia Commons. There are plenty of examples of institutions doing “GLAM-Wiki” activities, and several case studies to explore.

An example is the Ipiranga Museum from Brazil, which you can read about in this article by Wiki Movimento Brasil. Like the Rijksmuseum, the Ipiranga Museum had to close its premises for renovations, but they managed to open their collection through Wikimedia Commons and by integrating it into Wikipedia.

However, this integration may also attract funding from different sources. For example, the Sloan Foundation in the US supported the collaboration between DPLA and Wikimedia to make DPLA’s content more prominent in Wikimedia platforms.

Additionally, Wikimedia projects allow for very interesting ways in which your content can be enhanced. For example, take a look at the Wikidata Art Depiction Explorer, which allows for reusers to describe what is being depicted in a particular artwork.

Wikimedia projects are only one of the examples in which you could feature your content, but it is a prominent one given the fact that Wikipedia is the only website run by a non-profit to be among the top ten most visited websites on the internet. It is also a great platform in terms of what you can achieve if you connect wisely with the Wikimedia community. This means taking the time to understand how the platform works and what the avenues to connect with the community are. For example, if you want your collection to be on Wikipedia but you don’t have relationships with the Wikimedia community, consider hiring a Wikimedian in Residence (WiR), or dedicating staff time to engaging on Wikipedia and Wikimedia projects.

Foster reuse and remix culture

Putting your collections online can also allow for new creative works to be created. For example, that’s exactly what the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Black Hole Club and Cold War Steve Trust did with their campaign “Cut, Copy, Remix,” inviting artists to remix their openly available collection. And some of the results are quite amazing, like this “Cold War Steve vs The PRB, 2020” (Cold War Steve (Christopher Spencer), CC0. Photomontage commissioned by Birmingham Museums Trust.)

“Cold War Steve vs The PRB, 2020” (Cold War Steve (Christopher Spencer), CC0. Photomontage commissioned by Birmingham Museums Trust.)

There are other examples, such as the Rijksstudio award, that encourages people to remix their collections and even encourages them to be used and applied on everyday items. Others, such as the Library of Congress of the US, encourage people to explore their public domain catalog of music and become “Citizen DJs.” And others, such as the Coding Da Vinci project in Germany and The Heritage Lab in India, encourage reusing cultural data as a way to explore and reuse collections.

This selected set of cases shows how important it is to allow users to engage on their own terms and to explore the wide range of possibilities only limited by their own imagination.

Aim for accessibility

In her article “The Marrakesh Treaty: challenging GLAMs to generate readable documents for people with disabilities” Argentinean librarian Virginia Simón identifies some ways in which GLAMs can help make works more accessible for people with disabilities. Engaging diverse users is one of the main benefits that come with digital cultural heritage. Explore different ways in which open access can allow for providing new experiences for users.

Crowdsourcing & volunteering

Another important aspect of open access is that it gives new opportunities for communities to engage with your collections and content. Engagement with communities can be achieved through crowdsourcing tasks or through working with volunteers in different content campaigns, among other examples. This contributes to overall better engagement of citizenship and communities with cultural heritage.

However, this is not to say that by crowdsourcing tasks there is no effort involved. Normally, crowdsourcing requires a lot of time from the institution, to prepare in advance the content or collections that might be used in crowdsourcing tasks or content campaigns.

As an example, see what Siobhan Leachman has to share. Siobhan is a very active community member of Wikimedia projects. Siobhan participates as a volunteer for the Biodiversity Heritage Library and the Smithsonian Transcription Center. She is also very vocal about which projects she decides to invest her time in, as described in this tweet:

In 2016, Siobhan gave a talk called “Crowdsourcing & how GLAMs encourage me to participate” at the National Digital Forum. In that talk, she gave three suggestions for GLAMs who want to attract people like her to collaborate:

-

- Be generous with your CONTENT: allow for volunteers contributing to your projects to play with your content and your data, download it, reuse it, and place it in other websites and projects where they are collaborating;

- Be generous with your TRUST: allow for volunteers to go right away into hands-on projects; make it easy for them to participate; design concrete, achievable tasks they can accomplish; allow for feedback and improvement, and be forgiving of mistakes;

- Be generous with TIME: implement different communication channels (social media, online meetings, office hours) where volunteers can reach out to you and chat about what they are doing and what excites them about their volunteer project; establish collaboration.

More importantly, as Siobhan noted, “Crowdsourcing isn’t about getting free labor. It’s about being open to your volunteers, ideas, and contributions. It’s about collaboration, and collaboration requires communication.” This is what we refer to in this section around planning for allocating proper resources to build these relationships!

Another amazing example of collaboration in Open Culture is the NEO Lab at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg. The NEO Lab “aims to explore new ways of working together – both internally and with different communities outside the museum – in order to transform how stories are told and how collections are conceived and used.”

What other cultural heritage projects do you know that are incorporating the value of collaboration? Which ones do you like? Have you thought about implementing a crowdsourcing project at your institution?

Evaluate your impact

Evaluating your impact is crucial to understand if the resources are being properly allocated. It also allows you to advocate internally for the importance of putting more resources into building digital capabilities.

Your impact will always be dependent on your goals, but an important part of evaluating that impact will be to track reuse. Well-resourced institutions might be able to track their impact by deploying tracking tools, such as the work that the Cleveland Museum of Art is doing with their CMA dashboard.

But even if you do not have those resources, you can still do things to measure your impact. For example, you can offer ways for people to give you feedback on how they are using and reusing the cultural heritage you make openly available online. Offer avenues for people to tell their story about how they value and appreciate what you are doing.

By encouraging users to refer back to you in their credit statements, you might also be able to get a better overview of how, where, and by whom your collection is being reused to inform your impact evaluations.

Final remarks

Communicating your copyright policies clearly is fundamental to allowing communities to reuse your content. There are many ways in which different communities can engage with your content. Tracking some of these reuses allows you to build your case on how releasing your collections and content has a broad impact.

- The text reads: “What is the Smithsonian's commitment to cultural responsibility with open access? The Smithsonian respects the rights and sovereignty of the diverse cultures Smithsonian collections represent. The Smithsonian engages with these communities about the use of these assets, so culturally sensitive content may not be Open Access now or in the future. Please view the Smithsonian Open Access Values Statement to learn more about the Smithsonian’s core values in adopting and executing the Open Access Initiative, now and going forward. Please note that the language and terminology used in this collection reflects the context and culture of the time of its creation, and may include culturally sensitive information. As an historical document, its contents may be at odds with contemporary views and terminology. The information within this collection does not reflect the views of the Smithsonian Institution, but is available in its original form to facilitate research. For questions or comments regarding sensitive content, access, and use related to this collection, please contact openaccess@si.edu” ↵